GAMIFYING PET CARE

Pet Quest

BRIEF

We designed a gamified app to help kids care for pets—task tracking, rewards, parent dashboard. It worked mechanically, but user testing revealed we might be teaching kids to ask "what's in it for me?" instead of building genuine empathy. I didn't solve this tension, but naming it changed how I think about behavioral design.

TEAM

Will Lovelace

Josie Welin

FOCUS

Concept-

Development

Interaction- Design

DURATION

2 Weeks

YEAR

2025

We built an app to teach kids responsibility.

Parents set up tasks—feed the dog, clean the litter box, walk the cat. Kids complete them, earn rewards, everyone's happy. Classic behavioral design. Gamification 101.

Except we accidentally designed a system that might teach kids the exact opposite of what we intended.

This choice mattered

Canvas isn't just a visual design problem. It's an information systems problem with a built-in conflict: professors want autonomy, students want consistency. That tension would end up teaching us more than any amount of pixel-pushing ever could.

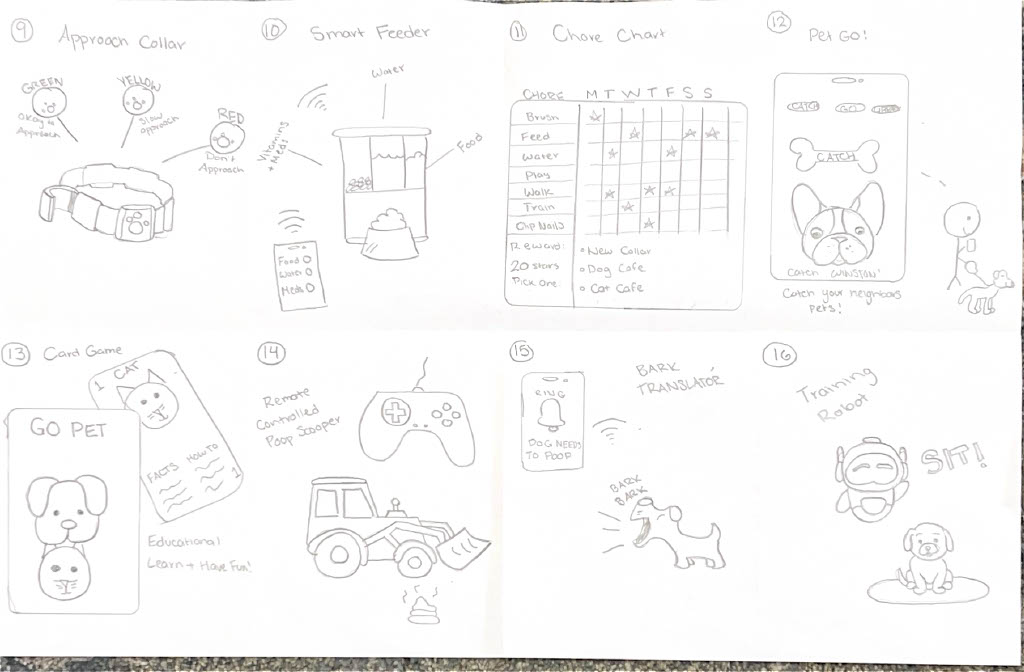

The assignment gave us categories, not solutions

Pick a domain—health, education, pets, fitness—and design something that solves a problem within it. My team chose pets immediately. We all loved animals, and we'd all seen the same pattern: kids beg for a puppy, promise to take care of it, then forget it exists after two weeks. Parents end up doing all the work.

We saw an opportunity. What if there was an app that helped kids actually follow through? Task tracking, reminders, accountability. Make caring for pets easier and more consistent.

The problem felt clear. The solution felt obvious. We were wrong about what we were really designing.

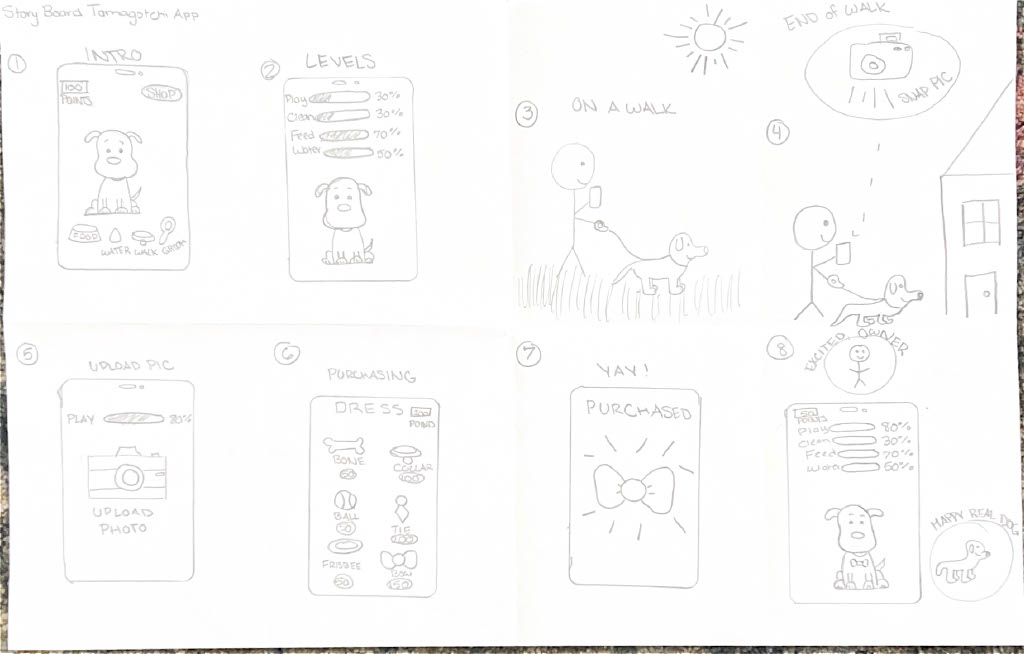

We started with extrinsic motivation

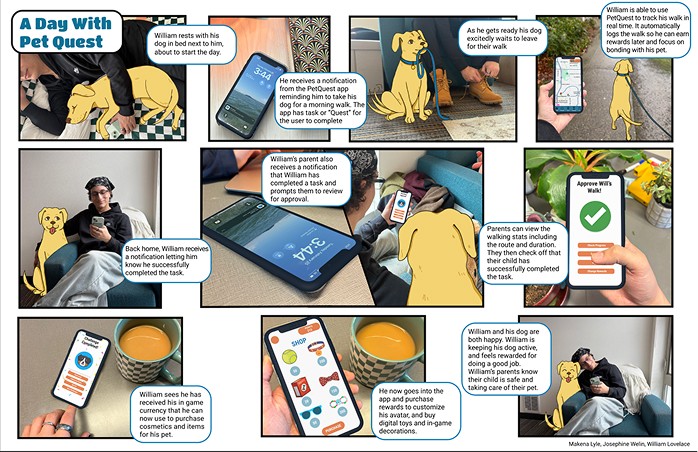

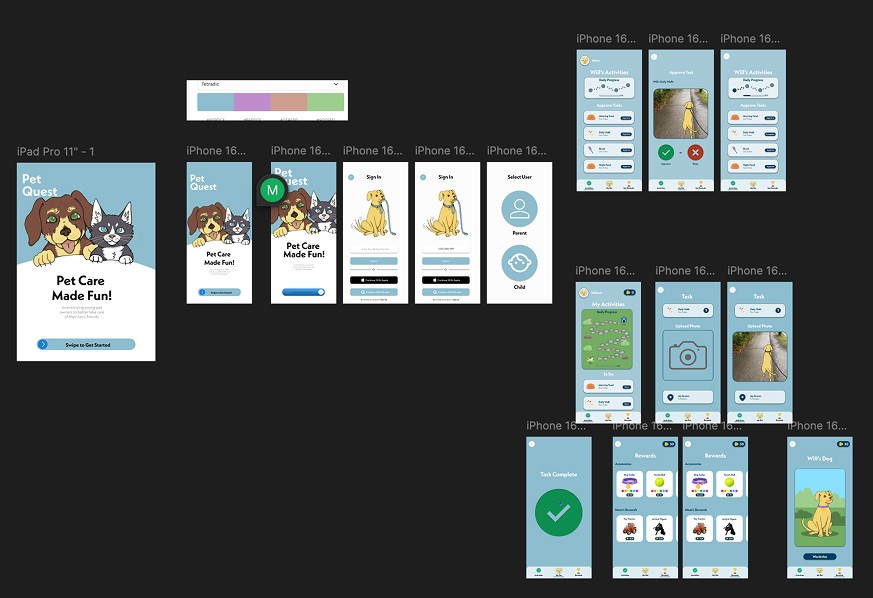

Task tracking for kids. Parent dashboard for oversight. A reward system that let families customize prizes—extra screen time, allowance money, trips for ice cream. Complete your tasks, earn currency, unlock rewards. We built digital avatars that kids could customize, with the option for parents to layer on real-world incentives if they wanted.

The mechanics worked beautifully on paper.

Then we tested with actual families

Some parents loved it. Finally, a way to get their kids to actually walk the dog without constant nagging. Others immediately saw the trap: "I can't afford to give my kid rewards every time they feed the dog" or "I don't want to teach them they only get paid for doing what they should already be doing."

That second comment hit different. Not because it was about affordability—we'd already solved that with the hybrid digital/physical reward system. But because it named the thing I'd been quietly worrying about for weeks: Are we teaching kids that the only reason to care for a pet is to get something in return?

Extrinsic motivation works beautifully. Short-term. You can absolutely get a kid to walk the dog for a week if there's a prize at the end. Gold stars, screen time, whatever. The behavior happens. Parents are thrilled. Problem solved, right?

But does that create a lifelong habit of caring for animals? Or does it just train them to ask "what's in it for me?" every time something needs their attention?

I raised this with my team. We talked about it in our debrief meetings. We acknowledged the tension in our final presentation. But we didn't solve it. We shipped an app that worked mechanically—tasks got completed, parents got compliance, kids got rewards—without addressing whether we were actually teaching empathy or just gamifying obligation.

Looking back, there were ways to mitigate it

We could've built in reflection prompts: "How do you think Max felt after his walk today?" We could've unlocked story content about why pets need care, not just what tasks needed doing. We could've designed moments where the app helps kids notice their pet's behavior changes—how the dog gets excited when they come home, how the cat purrs when they're gentle.

But we were so focused on making the mechanics work—parent dashboard, task tracking, reward systems, avatar customization—that we didn't prioritize the values piece. We treated empathy as a nice-to-have instead of the core feature.

My role:

I led the interaction design and built most of our prototypes. I mapped the parent and kid flows, designed the task completion states, and ran the usability tests that revealed the reward system backlash. I was also the one who kept bringing up the ethics question in team meetings, which honestly made me feel like I was being difficult when everyone else just wanted to ship something that worked.

In retrospect, being difficult about this was the most important thing I did. Not because we solved it—we didn't—but because naming the tension mattered more than pretending it didn't exist.

What I'd do differently

If I ran this project again, I'd design for intrinsic motivation first, extrinsic second. Maybe the app teaches kids to read their pet's body language. Maybe it creates moments of genuine connection—"Take a photo of your pet's favorite spot" or "What does your dog do when they're happy?"—instead of just checking boxes. Maybe the reward isn't currency or screen time but seeing your pet thrive because of your care.

I don't know exactly what that looks like. But I know we didn't build it this time.

I'd also push back harder on the project scope. We were designing an MVP in ten weeks, which meant shipping something functional took priority over shipping something thoughtful. Given more time, I'd have spent at least three weeks prototyping different motivation models and testing them with families. Does a reflection-based approach actually work with 8-year-olds, or do they need the dopamine hit of immediate rewards? Can you layer both? What's the balance?

Here's what was actually challenging about this project

Most design projects have a right answer you can test your way toward. This one had competing values with no clean resolution. Parents needed compliance (kids doing tasks without being asked). Kids needed motivation (a reason to care when it's cold outside and the dog needs walking). Pets needed consistent care (regardless of whether the kid feels like it that day).

We optimized for compliance and got it. But we didn't design for empathy, and that's the harder problem.

What this taught me

Not every design problem has a solution you can A/B test your way into. Sometimes you're working with human behavior and ethics, and the best you can do is:

Recognize the tension exists

Make intentional trade-offs

Be honest about what you didn't solve

I learned that "we shipped it and it works" isn't the same as "we solved the right problem." I learned that behavioral design has real consequences when you're shaping how kids learn to care for living things. And I learned to be less afraid of admitting when I don't have all the answers—because naming the problem is sometimes more valuable than pretending you solved it.